Been There, Done That

Far from offering vindication, the PNAS paper actually cuts the legs out from under Behe’s claims about evolution and the malaria parasite. How could he and his supporters get it so wrong? It may help to know that this is not the first time they’ve done something like this.

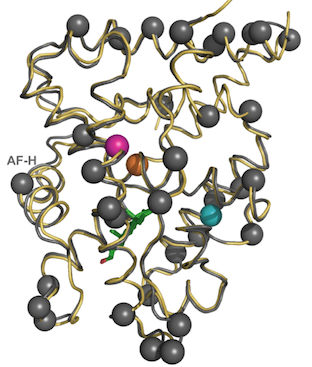

One of the leaders in the study of protein evolution is Joe Thornton, now at the University of Chicago. Over the past decade, Thornton and his colleagues have patiently teased out the evolutionary pathways that gave rise to a handful of important proteins. One of these is the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a protein that binds to hormones like cortisol and then alters patterns of gene expression in response to the presence of the hormone. In working out these pathways, Thornton’s lab has shown that the modern GR protein has its roots in an ancient protein that is the common ancestor of a number of other receptors, including those for testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. As their studies continued, they explored the specific pathways leading from that common ancestral receptor to the modern GR protein, and found that chance events, many of them highly improbable, played key roles in GR evolution.

This is hardly surprising. The role of contingency in evolutionary processes has been long appreciated (see Stephen Jay Gould’s book “Wonderful Life” for a popular treatment of this theme). However, the work of the Thornton lab has given contingency a much more specific biochemical and biophysical basis. In one of their most recent studies, Thornton and coauthor Michael J. Harms showed evidence that a specific series of “permissive” mutations were necessary for the evolution of the modern GR protein. They summarized the contingent nature of these mutations by pointing out that the identical series of mutations would be highly unlikely to evolve a second time:

If evolutionary history could be replayed from the ancestral starting point, the same kind of permissive substitutions would be unlikely to occur. The transition to GR’s present form and function would probably be inaccessible, and different outcomes would almost certainly ensue. Cortisol-specific signaling might evolve by a different mechanism in the GR, or by an entirely different protein, or not at all; in each case, GR—or the vertebrate endocrine system more generally—would be substantially different. (Harms & Thornton, 2014. Nature 512: 203-207).

Almost immediately, Michael Behe pounced on the work, proclaiming “that severe problems face even relatively minor Darwinian evolution of proteins.” According to the title of Behe’s web posting, Thornton’s recent work provides “More Strong Experimental Support for a Limit to Darwinian Evolution.” He writes, “The paper's conclusion is that, of the very large number of paths that random evolution could have taken, at best only extremely rare ones could lead to the functional modern protein.”

Now, Behe is right that only a few rare paths could lead to the modern protein, meaning the exact form of the GR protein we see today, but he is completely mistaken in seeing this as a “problem” for evolution. Thornton has been the victim of Behe’s distortions so many times before that back in 2009, at the urging of science writer Carl Zimmer, he responded with in detail (The complete letter is available here). Here are a few highlights from that letter to Zimmer:

Thanks for asking for my reaction to Behe’s post on our recent paper in Nature. His interpretation of our work is incorrect. He confuses “contingent” or “unlikely” with “impossible.” He ignores the key role of genetic drift in evolution. And he erroneously concludes that because the probability is low that some specific biological form will evolve, it must be impossible for ANY form to evolve.

A path to a new function that involves neutral intermediates is entirely accessible to the evolutionary processes of mutation, drift, and selection. Our work showed that these classic neodarwinian processes are entirely adequate to explain the evolution of GR’s new function.

Behe erroneously equates “evolving non-deterministically” with “impossible to evolve.” He supposes that if each of a set of specific evolutionary outcomes has a low probability, then none will evolve. This is like saying that, because the probability was vanishingly small that the 1996 Yankees would finish 92-70 with 871 runs scored and 787 allowed and then win the World Series in six games over Atlanta, the fact that all this occurred means it must have been willed by God.

Behe’s argument has no scientific merit. It is based on a misunderstanding of the fundamental processes of molecular evolution and a failure to appreciate the nature of probability itself. There is no scientific controversy about whether natural processes can drive the evolution of complex proteins. The work of my research group should not be misinterpreted by those who would like to pretend that there is.

I’m not sure that anyone could put it more succinctly than Thornton did in his 2009 letter, and yet five years later neither Behe nor his friends at the Discovery Institute get it. The misunderstanding (or is it misrepresentation?) of protein evolution and probability continues. Clearly it serves the purposes of the ID movement to pretend that the odds are hopelessly stacked against evolution when all the evidence indicates otherwise.

In a 2012 interview with Nature, Thornton expressed weariness with the way in which ID proponents continue to take issue with the clear implications of his work. “I’m sort of bored with them,” he told the journal. In truth, I am, too. Time after time, they take work that devastates their key claims, like the PNAS study on drug resistance in malaria, and pretend to their willing adherents that science is trending their way. As it misrepresents one study after another, the ID movement continues on its steady and certain downward slide to irrelevance.

Time

to Apologize?

In July of this year, Casey Luskin, professional spokesman for the Discovery Institute, demanded that Behe’s critics apologize to him. I certainly do agree with Mr. Luskin that an apology is in order, but it’s not the one he’s been demanding.

The real apology, which is long overdue, should be promptly sent out to all of those who have been taken in by Luskin’s and Behe’s continuing misrepresentations and distortions of the science of protein evolution. Knowing the Discovery Institute, however, I’m not holding my breath waiting for it.